Eduvation Blog

Thursday, September 19, 2013 | Category: Sharp Thinking

Peak Campus: 6 Converging Trends

By Ken Steele

Six predictable and long-term demographic, economic, technological and political trends mean that the majority of Canadian universities will face a challenging phenomenon I call “peak campus” within the next ten to fifteen years. Some northern Canadian universities already have a taste of it, thanks to declining demographics, while a second wave still lies ahead. Canada’s universities have become accustomed to managing budgets using increasing scale to compensate for steadily declining per-capita funding. But like a business model dependent on increasing volume to compensate for declining margin, this strategy will ultimately prove unsustainable, will put downward pressure on quality, and may well make universities vulnerable to both disruptive and traditional competitors.

Undergraduate enrolments at Canadian universities have been growing fairly steadily for half a century, from just a quarter million in the early 1960s to more than a million today, partly because of the baby boom and echo boom generations, and partly because of steadily rising participation rates. In fifty years, Canada’s universities have evolved from serving the most capable tenth of high school graduating classes, to serving almost three times as much of the population. Even setting aside debate over high school grade inflation, self-evidently the undergraduate population has changed significantly. On average, Canadian undergraduate tuitions have more than doubled since 1990,1 freshman class sizes have grown and become more dependent on multiple-choice exams, online plagiarism detection, adjunct faculty and teaching assistants. The majority of students are more careerist and credentialist than ever while less academically prepared, and are gravitating toward professional programs and reacting (or over-reacting) to every apparent shift in the labour market. Participation rates cannot grow indefinitely without impacting academic quality, and some academics argue that the trend has already passed the tipping point.2

Understandably, Canada’s universities sell themselves to government funders as vital economic engines of research and development, and as training grounds for the skilled, creative workforce of the future. To justify rising tuitions, universities simultaneously sell themselves to prospective students and parents on the basis of improved personal career earnings, also true (on average). But ever-increasing emphasis on career return-on-investment steers students toward academic programs with the most promising employment outcomes and starting salaries, and away from the liberal arts and sciences that were historically the foundation of our universities. Small wonder that arts and science enrolments are weakening at many remote university campuses: this is a glimpse of things to come.

There are six major trends that will converge over the next fifteen years to bring “peak campus” to the majority of Canadian universities:

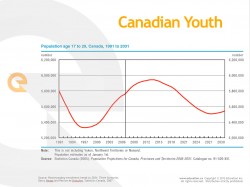

1. Declining Youth Demographics

Although universities have worked diligently to serve a broadening range of non-traditional students, two-thirds of undergraduate enrolment growth in the past three decades has come from increasing the participation rates of traditional-aged students.3 And as demographers are fond of reminding us, age-based trends are extraordinarily predictable: all the 18-year-olds who could possibly enrol in 2030 have already been born. While youth populations are steady or growing in the greater Toronto, Calgary and Vancouver areas, the vast majority of Canada can expect flat or declining youth cohorts for the next decade or more: Statistics Canada forecasts a decline of more than 400,000 youth between 2013 and 2028, and (based on current participation rates) a decline in university enrolment in every province, reaching about 65,000 nationwide.4 That is roughly equivalent to the full-time undergraduate enrolment of the 35 smallest universities included in the Maclean’s Guide. We’re already seeing the impact of declining demographics on enrolments in the Arts at UPEI, for example, where there has been a 22% decline in enrolment in a single year.

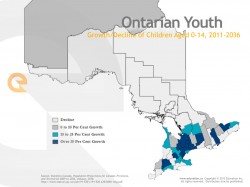

2. Intensifying Urbanization

Increasingly, Canada’s teenage population will be new Canadians or children of new Canadians, concentrated in a handful of major metropolitan centres and less willing to relocate for university than their predecessors.5 Universities located further than a two-hour drive from those growing centres will be facing enrolment challenges very soon. Some smaller universities and colleges are already leaning on international recruitment to counterbalance declining domestic enrolments, and in a handful of programs at several universities, international enrolments already exceed 25%. Many administrators and faculty believe there are practical limits to internationalization, either because of the expense of providing adequate international student support services, or the waning appeal of institutions drawing too heavily from a few international source countries.

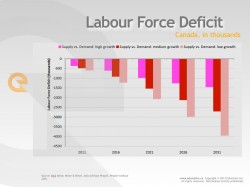

3. The Labour Market Pendulum Swings Back

Recent years have seen record-breaking youth unemployment and substantial retraining needs for displaced manufacturing workers in Canada, temporarily swelling PSE enrolments, particularly in career-oriented college programs. But labour force projections all seem in agreement: by 2030 Canada will face a workforce deficit of as many as four million skilled workers, and the effects will begin to be felt as early as 2020.6 Expect more government policy and employer initiatives to retain retired talent, to increase the workforce participation of under-represented groups, to attract more skilled immigrants – and likely also to attract young people to the labour force sooner, and support them through on-the-job training or employer-funded continuing education. The recent history of Northern Alberta provides an instructive example of the implications of workforce shortages: rising wages for service jobs, declining high school completion, rising interest in distance education, and delayed entry to university. It was no coincidence that one of Canada’s largest distance educators, Athabasca University, grew in such fertile soil, nor that the University of Alberta has started exploring the possibilities of modular certificates that could be assembled into a degree over time. In a future of workforce deficits, we will likely see more of what BCIT president Don Wright calls “modularized and just-in-time human capital development.”7

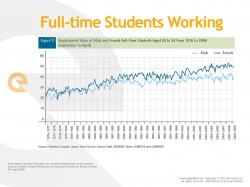

4. Part-Time Students, By Any Other Name

Since 1977, the percentage of full-time students on Canadian campuses who are also working at paid employment has risen gradually from 22% to 50%,8 and other studies report that undergraduate time spent on learning outside of class has declined from 25 to as little as 15 hours per week.9 Already, the majority of students registered as “full-time” undergraduates are in effect part-time students. A growing share of urban students intend to commute to campus, are seeking co-op or work-integrated learning opportunities, and will find it difficult to resist career opportunities as the labour market heats up. These students will find ways to spend less time on campus, a tendency that will be accelerated by new technologies.

5. Virtualization of Campus

Current undergraduate students are sometimes surprisingly conservative: given the choice, few would opt for webcast lectures or electronic textbooks in place of their traditional equivalents. Yet studies of learning outcomes consistently find that students retain 15% more content from a recorded lecture than a live one, and new intelligent textbooks achieve better success rates in math courses than traditional teaching models. Completing a degree online requires a level of motivation and discipline that is beyond most traditional undergraduate students, but most have completed a course or two online, and more than 400,000 non-traditional students are willingly paying twice the tuition of a public university to pursue a degree with online convenience. Over the next decade, as technology continues to evolve, students juggling employment or seeking to minimize their commutes will increasingly embrace online delivery.

In the near term, the imminent technological evolution is hybrid delivery, the augmentation of traditional face-to-face learning by online resources. The most dramatic results are achieved by “inverting the classroom,” assigning recorded lectures as homework and using class time for engaged, interactive learning. A study at UBC found that such active learning almost doubled exam performance and improved attendance by 20%.10 Given the choice, more than 80% of undergrads would appreciate access to recordings of the live lectures in their classes.11 Without question, the next few years will see rapid, wide-scale adoption of hybrid delivery of university courses; some institutions have already made public pledges to be 100% hybrid within the next year. Eventually, large lecture halls will become as outmoded as overhead projectors, and the world’s best academic communicators will publish definitive lectures to a global audience, like leading textbooks are published today.

Lecture capture, hybrid delivery, online courses, smart textbooks, virtual libraries, game-based learning, and more: students and faculty may resist some of these new technologies for a while, but escalating public demands for efficiency and access make the overall trend inescapable. Over the next decade or two, these emerging technologies will transform undergraduate education for many students, and the campus will become steadily more virtualized.

6. Public Pressure for Transferability

Governments in jurisdictions around the globe are calling for greater access to university degrees, while funding fails to keep pace with campus growth. In 2008 and 2009, the governments of BC and Alberta granted university status to seven colleges. Last February, a leaked “3 cubed” policy paper from Ontario’s MTCU urged the adoption of the trimester system, online courses, and three-year degrees as ways to increase university throughput and efficiency. Last summer, the Ontario government pressed its 47 public postsecondary institutions to draft “Strategic Mandate Agreements,” promising $30 million in seed money to promising pilot projects that could improve productivity and accessibility, with particular emphasis on institutional differentiation and mobile learning. This February, the Ontario PC party published an even more radical vision for higher education that explicitly puts “college first,” proposes to increase the range of three-year college degrees, and to tie PSE funding to the employment outcomes of their graduates.

In the past six months, the governors of Texas, California, and Florida have all challenged their state university systems to deliver undergraduate degrees for less than $10,000 in total, including textbooks and four years’ tuition. In all three cases, the proposed solutions combine dual-credit high school courses, substantial numbers of transferable community college credits, and online university courses. In developed countries worldwide the prognosis is similar: declining government revenues, rising health care demands, and politicians motivated to ensure access and affordability more than academic quality. Public pressure to accept dual credits and college transfer credits will only continue to rise.

In recent months, MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) have risen from obscurity to headlines, with upstart companies like Coursera and Udacity joining the ranks of MIT OpenCourseWare and now Edx to offer free online university courses to the masses. Students can now take Harvard or MIT courses for free, pay a fee to take a challenge exam, and receive a credential for successful completion of the course. While Harvard and MIT are not yet recognizing the courses for credit, the American Council on Education (ACE) has just endorsed five Coursera MOOCs from Duke, UC Irvine, and uPenn for credit – meaning that ACE’s 1,800 member colleges may soon accept these courses for credit towards university degrees.

Trends in virtualization and transferable credits converge in the MOOC phenomenon, but there are signs of one more possible development: degree aggregators. Provincial governments have little sway over academic matters at Canadian universities, but they have demonstrated willingness to exercise their power to create new degree-granting institutions. In the US, 19 state governors collectively launched Western Governors University in 1997, to provide online courses but also to accept a variety of course credit, and to offer competency-based degrees. Provincial degree aggregators would allow students to combine course credit from colleges and universities, perhaps even from MOOCs, Advanced Placement high school courses, and prior learning credit from workplace experience, to attain a degree with maximum flexibility at minimal public expense. This may not come to pass in Canada in my lifetime, but political decisions are notoriously difficult to predict.

Converging on “Peak Campus”

All six of these converging demographic, economic, technological and political trends are controversial, and will have both champions and detractors. Regardless of their benefits and costs, however, all signs are that these trends are moving inexorably forward. Many of Canada’s public universities are strong, resilient institutions with considerable momentum, and with layers of financial, social, and political insulation that have protected them in the short term from the market shocks suffered by their American counterparts. But institutional leaders and government policymakers alike need to recognize that, over the next fifteen years, campus populations and physical infrastructure needs will plateau, decline, or grow more slowly at the majority of Canada’s universities. Budget planning cannot depend upon steadily rising enrolments. Lecture theatres are less of a priority than IT infrastructure. The role and skill sets of undergraduate faculty need to evolve. Remote universities need to establish distinctive program offerings and centres of excellence to preserve critical mass. Growing urban centres need additional undergraduate capacity.

The effects of the first wave of “peak campus” are already being felt at northern and rural universities, as youth demographics decline and immigration accelerates the urbanization of Canada, and this effect will only intensify over the next decade. Over the next two decades, as government resources continue to tighten and the workforce becomes a seller’s market again, a second wave of universities will experience flat or declining campus populations (if not student head-counts) because of part-time programming, virtualization, transferable credits and degree aggregation.

For several generations yet, there will likely remain a market for a select group of “destination” universities with prestige brands to offer Canadians the traditional, four-year, residential undergraduate experience that is the model for most of our campuses today. But I believe the market for undergraduate education is bifurcating, and by 2030 the larger group of students will be seeking flexible, efficient means to a credential while spending as little time on a campus as possible – and evolving technologies and government agendas will support them in finding it.

Notes

1 Based on Statistics Canada, Centre for Education Statistics data, average annual cost of undergraduate tuition in 2010 dollars, published in the CAUT Almanac of Postsecondary Education in Canada.

2 See for example: James Côté and Anton Allahar, Ivory Tower Blues: A University System in Crisis (University of Toronto Press, 2007); or Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses (University of Chicago Press, 2011).

3 AUCC, Trends in Higher Education, Vol. 1: Enrolment. 2011.

4 Darcy Hango and Patrice de Broucker, Postsecondary Enrolment Trends to 2031: Three Scenarios. Statistics Canada, 2007.

5 Academica Group’s UCAS survey of 40,000 Ontario university applicants in 2005 found that 46% of new Canadians and first-generation Canadian applicants intended to commute to university from home rather than relocate, compared to 24% of applicants from long-time Canadian families.

6 The most-cited study is Rick Miner’s 2010 report, People without Jobs, Jobs without People: Canada’s Labour Market Future (available at www.minerandminer.ca )

7 Don Wright, BCIT: Why? Who? What? Discussion Paper, published January 2012.

8 Anne Motte and Saul Schwartz, Are Student Employment and Academic Success Linked? Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation Research Note, April 2009.

9 Philip Babcock and Mindy Marks, Leisure College USA: The Decline in Student Study Time, American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, No 7, August 2010.

10 Louis Deslauriers, Ellen Schelew, and Carl Weiman, “Improved Learning in a Large-Enrolment Physics Class,” Science 332:6031, 13 May 2011.

11 In a survey of 36,950 students at 127 US colleges and universities, the Educause Center for Applied Research (ECAR) found that while just 4.4% of respondents would prefer exclusive IT, 82.8% would prefer moderate or extensive IT to augment their courses. Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2010.

Post Tags: Demographics, Internationalization, Labour Market, Part-Time Studies, Virtualization

All contents copyright © 2014 Eduvation Inc. All rights reserved.

11 Comments

Hi Ken. This is an excellent article. It does a great job describing the forces that are affecting the state of affairs in higher education especially in Canada. I think that anyone who may have had their head in the sand prior to reading this article will have to acknowledge that the world they thought they lived in is changing. Luddites take heed.

As educators we must find more innovative ways to become more efficient, effective, and accountable for the educational outcomes we are responsible for, or get off the tracks because the train is clearly leaving the station and our world is unquestionably changing.

Thanks, Tom, for being the first to comment! I welcome other responses and thoughts as well. Hoping to spark a bit of conversation…

Thanks Ken!

I find the preference for today’s undergraduate students for an “on-campus” experience to be fascinating. Students see value in meaningful social interactions inside the classroom and out that the virtual world has largely not delivered – so far.

The challenge and opportunity is to combine these new tools with centers of excellence, brand and geography to build a unique experience that differentiates the institution in the global marketplace.

The U.S. appears to be leading the charge in terms of virtualization and leveraging “brand”. However, I wonder what the Europeans – particularly Germany is doing with respect to “the applied experience” and Tom’s points around educational outcomes?

Thanks for contributing to the discussion, Forrest.

Absolutely, there will continue to be a market for the traditional, on-campus student experience — although all indications are that this market segment will decline, not grow, in the decades ahead. Centres of excellence, branding, institutional positioning or differentiation can all offer institutions a chance to forestall the inevitable, although it will remain a zero-sum game competing for traditional full-time students. This will be survival of the fittest, or survival of those fortunate enough to be located near major immigration centres.

Excellent summation of where tertiary education is heading in Canada. It begs the following questions: How can Canadian universities make themselves relevant to the needs of this changing face of employment, and how do they best prepare their learners to have significant competitive advantage in the workplace ? By making themselves as stated, ‘destination universities’, known for specializing in areas where their graduates are able to differentiate themselves by their unique educational experience ( e.g. Leadership) and in providing access to a broad range of stimulating, current and diverse sources of learning to engage their adult learners giving them the intellectual tool kit for an ever changing world.

Thanks for contributing, Deb.

I hope that each institution can arrive at a slightly different answer to your question, finding disciplinary or interdisciplinary foci, pedagogical approaches, or other differentiations that also give their graduates distinct competencies. The answer for some students will be a truly “liberating” liberal arts education, while for others it will be much more career-focused work-integrated learning, or even early undergraduate research opportunities, international exchanges, or community service learning…

What I find encouraging is the scope of experimentation and variation in higher ed right now – which is part of the rationale for assembling the IdeaBank on pedagogy.

thanks for the insight. cool picture too. where is it from?

Thanks Andrew. The pic is a stock photo we purchased, by John Braid, of Whitby Abbey in North Yorkshire. We kept coming back to that particular abbey, as a haunting and beautiful example of gothic architecture that evokes the architecture of many traditional university campuses. A thousand years ago, it was the religious institutions that fell into disrepair for a variety of political reasons. We can only hope that academic institutions don’t face the same sort of neglect over the next few centuries…

In addition to your comments about international students, some of my recent reads suggest that with improvements to the education systems back home (where ever that might be) reduces the competitive advantage offered by a North American education. It seems pretty obvious that will translate to a reduction in international students … eek … more bad news!

Thanks Phil, and yes, as PSE in Brazil, India and China develops, there will be less push to go abroad from those markets. And recent reports suggest that students who have graduated from US schools don’t find it as big an advantage back in Asia as they had hoped.

But with overall doubling of the international student market projected, the first limitation on Canadian institutions will be their capacity to absorb and support international students. I think there’s a very real practical limit around 25-30% of the student body being international.

Great overview Ken. We’re already seeing some of these trends in Northern Ontario. I would say that we are also seeing some important nuances though. We are finding an interest in and willingness to take distance courses, but that manifests itself mostly AFTER students have gained confidence and skills through some face to face experiences. Also, we are seeing the interest in all the distance learning, credit recognition, credit transfer and so on among mature learners. Very little is evident among the 18-24 year old age group.

Finally, the trend away from arts and humanities is troubling since it represents the key form of education for citizenship and for leading thoughtful lives. We lose a key component of the social fabric of society when we focus only on the utility of professional programs and forget the accumulated wisdom of the arts and humanities.